Jump to Recent Airdates

Upcoming

Dorothy Butler Gilliam - S11 E7

Premiered On: 10/30/2015

Renee speaks with journalist Dorothy Butler Gilliam, who was the first African-American female reporter at The Washington Post. She retired in 2003 after a 35-year career with the paper.

- Friday April 26, 2024 2:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Friday April 26, 2024 1:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Friday April 26, 2024 5:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Friday April 26, 2024 4:30 pm CT on KETKY

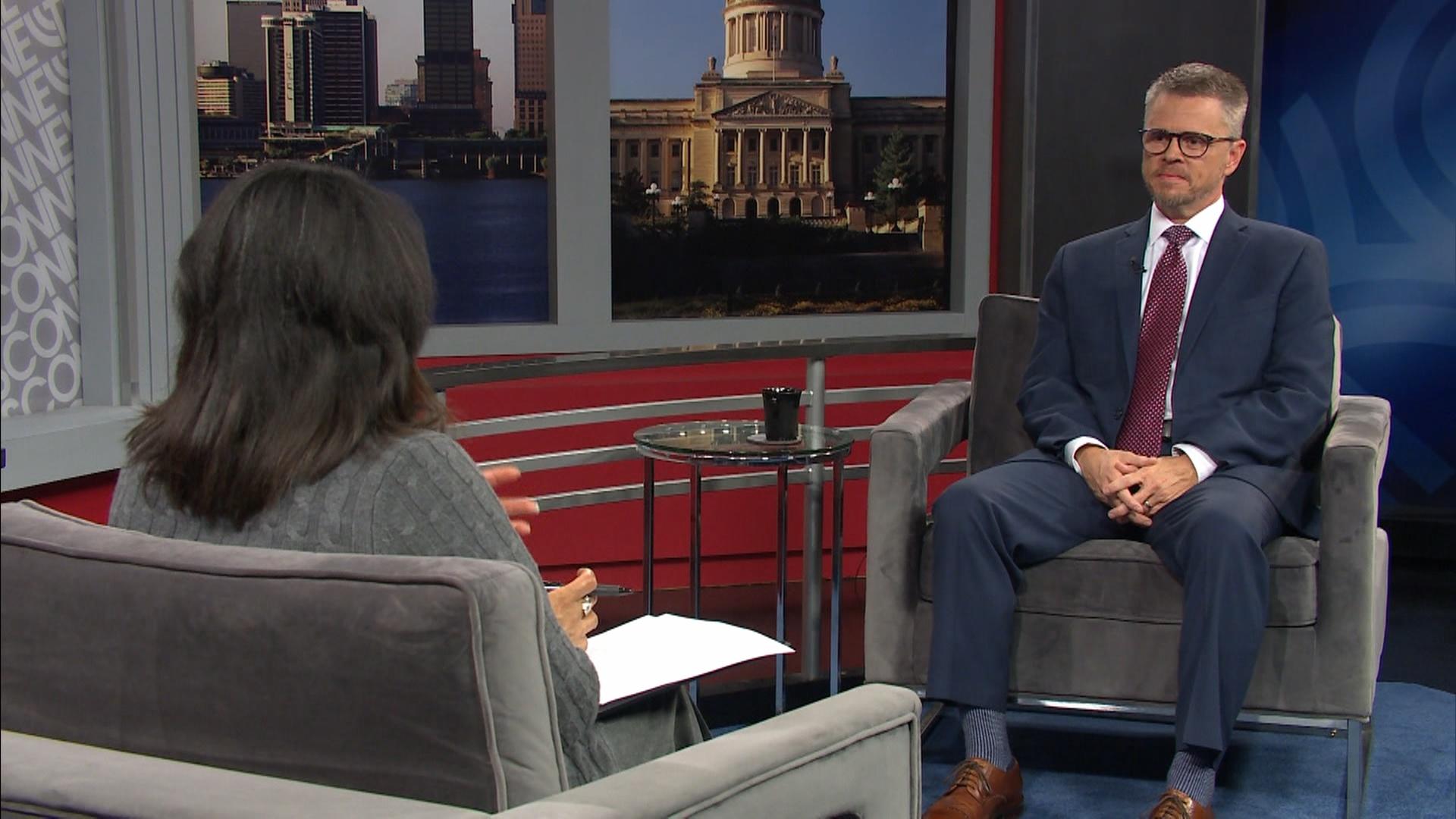

Kentucky Senate Majority Leader Damon Thayer - S19 E26

The regular session of the Kentucky General Assembly for 2024 has ended, and Senator Damon Thayer, who served for 22 years, including 12 as majority floor leader, will not be returning, the Georgetown senator is moving on. Renee Shaw and Sen. Thayer discuss some of the new laws passed this session and his activism on the campaign trail this spring. A 2024 KET production.

- Saturday April 27, 2024 4:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Saturday April 27, 2024 3:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Sunday April 28, 2024 8:00 am ET on KETKY

- Sunday April 28, 2024 7:00 am CT on KETKY

Podcaster Mario Maitland, Photographer Carol Peachee - S19 E27

Renee Shaw talks with up-and-coming digital content creator Mario Maitland, who is working with Kentucky Sports Radio, about hosting his own podcast. Next, photographer Carol Peachee talks about her new book "Shaker Made," which captures the cultural artifacts of Shaker Village at Pleasant Hill. A 2024 KET production.

- Sunday April 28, 2024 11:30 am ET on KET

- Sunday April 28, 2024 10:30 am CT on KET

- Sunday April 28, 2024 4:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Sunday April 28, 2024 3:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Sunday April 28, 2024 6:00 pm ET on KET2

- Sunday April 28, 2024 5:00 pm CT on KET2

- Saturday May 4, 2024 4:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Saturday May 4, 2024 3:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Sunday May 5, 2024 8:00 am ET on KETKY

- Sunday May 5, 2024 7:00 am CT on KETKY

Allison Joseph - S11 E8

Premiered On: 11/06/2015

Allison Joseph is the author of six poetry books. She teaches at Southern Illinois University in Carbondale, Illinois, where she helped found {Crab Orchard Review}, a literary journal, and the Young Writers Workshop, a co-ed residential summer program for teen writers.

- Monday April 29, 2024 5:30 am ET on KETKY

- Monday April 29, 2024 4:30 am CT on KETKY

- Monday April 29, 2024 11:30 am ET on KETKY

- Monday April 29, 2024 10:30 am CT on KETKY

- Monday April 29, 2024 2:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Monday April 29, 2024 1:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Monday April 29, 2024 5:31 pm ET on KETKY

- Monday April 29, 2024 4:31 pm CT on KETKY

Ari Berman - S11 E9

Premiered On: 11/13/2015

Renee's guest is Ari Berman, a contributing writer for "The Nation" magazine and an Investigative Journalism Fellow at The Nation Institute. He has written extensively about American politics, civil rights and the intersection of money and politics. The title of his new book is "Give Us the Ballot: The Modern Struggle for Voting Rights in America". A 2015 KET Production.

- Tuesday April 30, 2024 5:30 am ET on KETKY

- Tuesday April 30, 2024 4:30 am CT on KETKY

- Tuesday April 30, 2024 11:30 am ET on KETKY

- Tuesday April 30, 2024 10:30 am CT on KETKY

- Tuesday April 30, 2024 2:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Tuesday April 30, 2024 1:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Tuesday April 30, 2024 5:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Tuesday April 30, 2024 4:30 pm CT on KETKY

Miss Kentucky Clark Davis - S11 E10

Premiered On: 11/20/2015

Renee speaks with Miss Kentucky Clark Davis, a sophomore at the University of Kentucky majoring in vocal performance, with a minor in political science. Davis was diagnosed with dyslexia in elementary school. Her pageant platform is dyslexia awareness. A 2015 KET Production.

- Wednesday May 1, 2024 5:30 am ET on KETKY

- Wednesday May 1, 2024 4:30 am CT on KETKY

- Wednesday May 1, 2024 11:30 am ET on KETKY

- Wednesday May 1, 2024 10:30 am CT on KETKY

- Wednesday May 1, 2024 2:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Wednesday May 1, 2024 1:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Wednesday May 1, 2024 5:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Wednesday May 1, 2024 4:30 pm CT on KETKY

Kentucky First Lady Jane Beshear - S11 E11

Premiered On: 12/11/2015

Renee speaks with Jane Beshear, former first lady of Kentucky, about her policy initiatives and programs during her time in the Governor's Mansion. A 2015 KET production.

- Thursday May 2, 2024 5:30 am ET on KETKY

- Thursday May 2, 2024 4:30 am CT on KETKY

- Thursday May 2, 2024 11:31 am ET on KETKY

- Thursday May 2, 2024 10:31 am CT on KETKY

- Thursday May 2, 2024 2:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Thursday May 2, 2024 1:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Thursday May 2, 2024 5:31 pm ET on KETKY

- Thursday May 2, 2024 4:31 pm CT on KETKY

Wayne Lewis - S11 E15

Premiered On: 01/15/2016

University of Kentucky professor Wayne Lewis, Ph.D., author of "The Politics of Parent Choice in Public Education" and the forthcoming, "Black Choice", talks about charter school legislation in Kentucky and its effectiveness in other states in narrowing the achievement gap. A 2016 KET Production.

- Friday May 3, 2024 5:30 am ET on KETKY

- Friday May 3, 2024 4:30 am CT on KETKY

- Friday May 3, 2024 11:31 am ET on KETKY

- Friday May 3, 2024 10:31 am CT on KETKY

- Friday May 3, 2024 2:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Friday May 3, 2024 1:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Friday May 3, 2024 5:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Friday May 3, 2024 4:30 pm CT on KETKY

Connections - S19 E28

- Sunday May 5, 2024 11:30 am ET on KET

- Sunday May 5, 2024 10:30 am CT on KET

- Sunday May 5, 2024 4:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Sunday May 5, 2024 3:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Sunday May 5, 2024 6:00 pm ET on KET2

- Sunday May 5, 2024 5:00 pm CT on KET2

- Saturday May 11, 2024 4:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Saturday May 11, 2024 3:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Sunday May 12, 2024 8:00 am ET on KETKY

- Sunday May 12, 2024 7:00 am CT on KETKY

Anthony Smith - S11 E16

Premiered On: 01/22/2016

Anthony Smith, CEO of Cities United, a national network of communities focused on eliminating violence related to African American males, talks about the violence-curbing initiatives he helped create in Louisville including the Right Turn program for teenagers 16 to 19 who have committed minor infractions that have landed them in the court system. A 2016 KET Production.

- Monday May 6, 2024 5:30 am ET on KETKY

- Monday May 6, 2024 4:30 am CT on KETKY

- Monday May 6, 2024 11:30 am ET on KETKY

- Monday May 6, 2024 10:30 am CT on KETKY

- Monday May 6, 2024 2:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Monday May 6, 2024 1:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Monday May 6, 2024 5:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Monday May 6, 2024 4:30 pm CT on KETKY

Andrew Brennen - S11 E17

Premiered On: 01/29/2016

Renee speaks with Andrew Brennen, national field director for Student Voice, a for-students-by-students nonprofit organization spearheading a social movement to integrate student voices into the global education conversation. He is also co-founder, director of the Student Voice Team at the Prichard Committee for Academic Excellence. A 2016 KET Production.

- Tuesday May 7, 2024 5:32 am ET on KETKY

- Tuesday May 7, 2024 4:32 am CT on KETKY

- Tuesday May 7, 2024 11:30 am ET on KETKY

- Tuesday May 7, 2024 10:30 am CT on KETKY

- Tuesday May 7, 2024 2:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Tuesday May 7, 2024 1:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Tuesday May 7, 2024 5:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Tuesday May 7, 2024 4:30 pm CT on KETKY

A Tribute to Georgia Davis Powers - S11 E18

Premiered On: 02/05/2016

In this special episode, Renee and her guests Raoul Cunningham, president of the Louisville NAACP, and State Sen. Gerald Neal celebrate the life and legacy of civil rights pioneer and former Kentucky Sen. Georgia Davis Powers, the first African-American and first woman elected to the Kentucky Senate. Powers died January 30, 2016 at the age of 92. The program features never-before-seen footage of an interview Renee conducted with Powers two years ago. A 2016 KET Production.

- Wednesday May 8, 2024 5:30 am ET on KETKY

- Wednesday May 8, 2024 4:30 am CT on KETKY

- Wednesday May 8, 2024 11:30 am ET on KETKY

- Wednesday May 8, 2024 10:30 am CT on KETKY

- Wednesday May 8, 2024 2:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Wednesday May 8, 2024 1:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Wednesday May 8, 2024 5:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Wednesday May 8, 2024 4:30 pm CT on KETKY

Child Abuse Awareness and Prevention - S11 E24

Premiered On: 04/08/2016

Jill Seyfred, executive director of Prevent Child Abuse Kentucky, discusses efforts to increase awareness and prevention of child abuse in the state. A 2016 KET Production.

- Thursday May 9, 2024 5:30 am ET on KETKY

- Thursday May 9, 2024 4:30 am CT on KETKY

- Thursday May 9, 2024 11:30 am ET on KETKY

- Thursday May 9, 2024 10:30 am CT on KETKY

- Thursday May 9, 2024 2:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Thursday May 9, 2024 1:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Thursday May 9, 2024 5:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Thursday May 9, 2024 4:30 pm CT on KETKY

Kentucky Secretary of State Alison Lundergan Grimes - S11 E25

Premiered On: 04/15/2016

Kentucky Secretary of State Alison Lundergan Grimes talks about her legislative agenda and the new online voter registration portal. A 2016 KET Production.

- Friday May 10, 2024 5:30 am ET on KETKY

- Friday May 10, 2024 4:30 am CT on KETKY

- Friday May 10, 2024 11:30 am ET on KETKY

- Friday May 10, 2024 10:30 am CT on KETKY

- Friday May 10, 2024 2:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Friday May 10, 2024 1:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Friday May 10, 2024 5:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Friday May 10, 2024 4:30 pm CT on KETKY

Connections - S19 E29

- Sunday May 12, 2024 11:30 am ET on KET

- Sunday May 12, 2024 10:30 am CT on KET

- Sunday May 12, 2024 4:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Sunday May 12, 2024 3:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Sunday May 12, 2024 6:01 pm ET on KET2

- Sunday May 12, 2024 5:01 pm CT on KET2

- Saturday May 18, 2024 4:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Saturday May 18, 2024 3:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Sunday May 19, 2024 8:00 am ET on KETKY

- Sunday May 19, 2024 7:00 am CT on KETKY

Crystal Wilkinson - S11 E26

Premiered On: 04/22/2016

Affrilachian poet and author Crystal Wilkinson talks about her first novel, "The Birds of Opulence", that tackles the issue of mental illness and the plight of the African American female experience in the South. A 2016 KET Production.

- Monday May 13, 2024 5:30 am ET on KETKY

- Monday May 13, 2024 4:30 am CT on KETKY

- Monday May 13, 2024 11:30 am ET on KETKY

- Monday May 13, 2024 10:30 am CT on KETKY

- Monday May 13, 2024 2:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Monday May 13, 2024 1:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Monday May 13, 2024 5:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Monday May 13, 2024 4:30 pm CT on KETKY

Dr. Erin Frazier - S11 E27

Premiered On: 04/29/2016

Renee's guest is Dr. Erin Frazier, a pediatrician with Kosair Children's Hospital in Louisville. She also serves as medical director at Children's Hospital Foundation Office of Child Advocacy and chair of the Partnership to Eliminate Child Abuse. Dr. Frazier discusses coping techniques for parents that can prevent child abuse. She specializes in educating parents and caregivers about the dangers of shaking infants and strategies for dealing with persistent crying babies. A 2016 KET Production.

- Tuesday May 14, 2024 5:31 am ET on KETKY

- Tuesday May 14, 2024 4:31 am CT on KETKY

- Tuesday May 14, 2024 11:30 am ET on KETKY

- Tuesday May 14, 2024 10:30 am CT on KETKY

- Tuesday May 14, 2024 2:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Tuesday May 14, 2024 1:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Tuesday May 14, 2024 5:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Tuesday May 14, 2024 4:30 pm CT on KETKY

Gretchen Hunt - S11 E28

Premiered On: 05/06/2016

Renee's guest is Gretchen Hunt, who heads the Office of Victims Advocacy within the Office of the Kentucky Attorney General. She talks about recent legislative successes in protecting women from violent crime. Hunt was a leader in helping to advocate for passage of Kentucky's Human Trafficking Victims Rights Act. A 2016 KET Production.

- Wednesday May 15, 2024 5:30 am ET on KETKY

- Wednesday May 15, 2024 4:30 am CT on KETKY

- Wednesday May 15, 2024 11:30 am ET on KETKY

- Wednesday May 15, 2024 10:30 am CT on KETKY

- Wednesday May 15, 2024 2:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Wednesday May 15, 2024 1:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Wednesday May 15, 2024 5:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Wednesday May 15, 2024 4:30 pm CT on KETKY

Kishonna Gray - S11 E29

Premiered On: 05/13/2016

Renee's guest is Dr. Kishonna Gray, assistant professor in the School of Justice Studies at Eastern Kentucky University. She is also the founder and director of the Critical Gaming Lab housed in the School of Justice Studies. Dr. Gray also holds a joint position in Women & Gender Studies and is an affiliate faculty in the African/African-American Studies Program. Her research and teaching interests incorporate an intersecting focus on identity, culture, and new media. A 2016 KET Production.

- Thursday May 16, 2024 5:30 am ET on KETKY

- Thursday May 16, 2024 4:30 am CT on KETKY

- Thursday May 16, 2024 11:30 am ET on KETKY

- Thursday May 16, 2024 10:30 am CT on KETKY

- Thursday May 16, 2024 2:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Thursday May 16, 2024 1:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Thursday May 16, 2024 5:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Thursday May 16, 2024 4:30 pm CT on KETKY

Oral Health Care In Kentucky - S11 E30

Premiered On: 05/20/2016

Renee and her guests Lacey McNary, a health policy consultant and principal of McNary and Associates and Dr. Laura Hancock Jones, a dentist working with the UK College of Dentistry Public Health Division's Western Kentucky Dental Outreach Program and chair of the Kentucky Oral Health Coalition, discuss the state of oral health in Kentucky. Part of KET's "Inside Oral Health Care" initiative, funded in part by a grant from the Foundation for a Healthy Kentucky. A 2016 KET Production.

- Friday May 17, 2024 5:30 am ET on KETKY

- Friday May 17, 2024 4:30 am CT on KETKY

- Friday May 17, 2024 11:30 am ET on KETKY

- Friday May 17, 2024 10:30 am CT on KETKY

- Friday May 17, 2024 2:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Friday May 17, 2024 1:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Friday May 17, 2024 5:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Friday May 17, 2024 4:30 pm CT on KETKY

Connections - S19 E30

- Sunday May 19, 2024 11:30 am ET on KET

- Sunday May 19, 2024 10:30 am CT on KET

- Sunday May 19, 2024 4:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Sunday May 19, 2024 3:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Sunday May 19, 2024 6:00 pm ET on KET2

- Sunday May 19, 2024 5:00 pm CT on KET2

- Saturday May 25, 2024 4:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Saturday May 25, 2024 3:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Sunday May 26, 2024 8:00 am ET on KETKY

- Sunday May 26, 2024 7:00 am CT on KETKY

Jessie Laine Powell - S11 E31

Premiered On: 05/27/2016

Lexington-based national recording jazz artist Jessie Laine Powell performs and discusses her new album, "Fill the Void". Powell talks about how her teenage daughter inspired the song, "You're Okay." A 2016 KET Production.

- Monday May 20, 2024 5:30 am ET on KETKY

- Monday May 20, 2024 4:30 am CT on KETKY

- Monday May 20, 2024 11:30 am ET on KETKY

- Monday May 20, 2024 10:30 am CT on KETKY

- Monday May 20, 2024 2:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Monday May 20, 2024 1:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Monday May 20, 2024 5:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Monday May 20, 2024 4:30 pm CT on KETKY

Scott Hesseltine - S11 E32

Premiered On: 06/03/2016

Scott Hesseltine, vice president of addiction services at Seven Counties Services, discusses new models of treatment to help those with opioid abuse disorders recover. He also talks about a new facility that serves expectant mothers with addiction throughout their pregnancy with wraparound services to get them on the path to recovery. Part of KET's "Inside Opioid Addiction" initiative, funded in part by a grant from the Foundation for a Healthy Kentucky. A 2016 KET Production.

- Tuesday May 21, 2024 5:30 am ET on KETKY

- Tuesday May 21, 2024 4:30 am CT on KETKY

- Tuesday May 21, 2024 11:30 am ET on KETKY

- Tuesday May 21, 2024 10:30 am CT on KETKY

- Tuesday May 21, 2024 2:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Tuesday May 21, 2024 1:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Tuesday May 21, 2024 5:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Tuesday May 21, 2024 4:30 pm CT on KETKY

Dr. Lynne Saddler - S11 E33

Premiered On: 06/10/2016

Dr. Lynne Saddler, district director of health at the Northern Kentucky Health Department, talks about the heroin epidemic in Northern Kentucky. She discusses current community efforts and the impact of a syringe exchange program. Part of KET's "Inside Opioid Addiction" initiative, funded in part by a grant from the Foundation for a Healthy Kentucky. A 2016 KET Production.

- Wednesday May 22, 2024 5:30 am ET on KETKY

- Wednesday May 22, 2024 4:30 am CT on KETKY

- Wednesday May 22, 2024 11:30 am ET on KETKY

- Wednesday May 22, 2024 10:30 am CT on KETKY

- Wednesday May 22, 2024 2:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Wednesday May 22, 2024 1:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Wednesday May 22, 2024 5:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Wednesday May 22, 2024 4:30 pm CT on KETKY

Fayette County Veterans Treatment Court - S11 E34

Premiered On: 06/17/2016

Kathy Vasquez, veterans justice outreach specialist, and Elton Terry, recovery coordinator, with the Lexington VA Medical Center, talk about the Fayette County Veterans Treatment Court (FCVTC). The FCVTC program provides court-supervised treatment for veterans as an alternative to incarceration, services and treatments address substance abuse and/or mental health; connection to benefits; and help with housing, employment, and education. Part of KET's "Inside Opioid Addiction" initiative, funded in part by a grant from the Foundation for a Healthy Kentucky. A 2016 KET Production.

- Thursday May 23, 2024 5:30 am ET on KETKY

- Thursday May 23, 2024 4:30 am CT on KETKY

- Thursday May 23, 2024 11:30 am ET on KETKY

- Thursday May 23, 2024 10:30 am CT on KETKY

- Thursday May 23, 2024 2:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Thursday May 23, 2024 1:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Thursday May 23, 2024 5:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Thursday May 23, 2024 4:30 pm CT on KETKY

Jason Merrick - S11 E35

Premiered On: 06/24/2016

Jason Merrick, director of inmate addiction services at the Kenton County Detention Center, discusses the inmate drug and alcohol treatment program he launched consisting of counseling sessions, time for inmates to pursue their GED certificates, and attend 12-step programs. Part of KET's "Inside Opioid Addiction" initiative, funded in part by a grant from the Foundation for a Healthy Kentucky. A 2016 KET Production.

- Friday May 24, 2024 5:30 am ET on KETKY

- Friday May 24, 2024 4:30 am CT on KETKY

- Friday May 24, 2024 11:30 am ET on KETKY

- Friday May 24, 2024 10:30 am CT on KETKY

- Friday May 24, 2024 2:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Friday May 24, 2024 1:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Friday May 24, 2024 5:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Friday May 24, 2024 4:30 pm CT on KETKY

Connections - S19 E31

- Sunday May 26, 2024 11:30 am ET on KET

- Sunday May 26, 2024 10:30 am CT on KET

- Sunday May 26, 2024 4:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Sunday May 26, 2024 3:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Sunday May 26, 2024 6:00 pm ET on KET2

- Sunday May 26, 2024 5:00 pm CT on KET2

Kimberly Johnson - S11 E36

Premiered On: 07/01/2016

Renee's guest is Kimberly Johnson, Ph.D., director of the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment for the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). The Center for Substance Abuse promotes community-based substance abuse treatment and recovery services for individuals and families in every community. Taped at the SAMHSA headquarters in Rockville, Maryland, Renee talks with Dr. Johnson about the nation's reliance on high-powered pain killers to manage pain, addiction recovery models, drug abuse prevention, and more. Part of KET's "Inside Opioid Addiction" initiative, funded in part by a grant from the Foundation for a Healthy Kentucky. A 2016 KET Production.

- Monday May 27, 2024 5:30 am ET on KETKY

- Monday May 27, 2024 4:30 am CT on KETKY

- Monday May 27, 2024 11:30 am ET on KETKY

- Monday May 27, 2024 10:30 am CT on KETKY

- Monday May 27, 2024 2:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Monday May 27, 2024 1:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Monday May 27, 2024 5:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Monday May 27, 2024 4:30 pm CT on KETKY

U.S. Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack - S11 E37

Premiered On: 07/08/2016

From the USDA in Washington, D.C., Renee talks with U.S. Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack, who discusses the White House's response to the opioid addiction epidemic sweeping the nation, and the Obama Administration's budget proposal to invest more than $1 billion dollars in addiction treatment. Secretary Vilsack is personally familiar with addiction as he watched his adoptive mother struggle with drug use before she eventually found a path to sobriety. He and Renee discuss the challenges of treating addicts in rural areas, the connections between poverty and addiction, drug-monitoring programs to prevent doctor shopping, and the use of technology in recovery tools. Part of KET's "Inside Opioid Addiction" initiative, funded in part by a grant from the Foundation for a Healthy Kentucky. A 2016 KET Production.

- Tuesday May 28, 2024 5:30 am ET on KETKY

- Tuesday May 28, 2024 4:30 am CT on KETKY

- Tuesday May 28, 2024 11:30 am ET on KETKY

- Tuesday May 28, 2024 10:30 am CT on KETKY

Jump to Upcoming Airdates

Recent

Dorothy Butler Gilliam - S11 E7

- Friday April 26, 2024 11:30 am ET on KETKY

- Friday April 26, 2024 10:30 am CT on KETKY

- Friday April 26, 2024 5:30 am ET on KETKY

- Friday April 26, 2024 4:30 am CT on KETKY

Jacinda Townsend - S11 E6

- Thursday April 25, 2024 5:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Thursday April 25, 2024 4:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Thursday April 25, 2024 2:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Thursday April 25, 2024 1:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Thursday April 25, 2024 11:31 am ET on KETKY

- Thursday April 25, 2024 10:31 am CT on KETKY

- Thursday April 25, 2024 5:30 am ET on KETKY

- Thursday April 25, 2024 4:30 am CT on KETKY

Kellie Blair Hardt - S11 E5

- Wednesday April 24, 2024 5:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Wednesday April 24, 2024 4:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Wednesday April 24, 2024 2:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Wednesday April 24, 2024 1:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Wednesday April 24, 2024 11:30 am ET on KETKY

- Wednesday April 24, 2024 10:30 am CT on KETKY

- Wednesday April 24, 2024 5:31 am ET on KETKY

- Wednesday April 24, 2024 4:31 am CT on KETKY

Childhood Cancer - S11 E4

- Tuesday April 23, 2024 5:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Tuesday April 23, 2024 4:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Tuesday April 23, 2024 2:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Tuesday April 23, 2024 1:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Tuesday April 23, 2024 11:30 am ET on KETKY

- Tuesday April 23, 2024 10:30 am CT on KETKY

- Tuesday April 23, 2024 5:33 am ET on KETKY

- Tuesday April 23, 2024 4:33 am CT on KETKY

The Kentucky African American Encyclopedia - Gerald Smith - S11 E3

- Monday April 22, 2024 5:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Monday April 22, 2024 4:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Monday April 22, 2024 2:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Monday April 22, 2024 1:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Monday April 22, 2024 11:30 am ET on KETKY

- Monday April 22, 2024 10:30 am CT on KETKY

- Monday April 22, 2024 5:30 am ET on KETKY

- Monday April 22, 2024 4:30 am CT on KETKY

Kentucky Senate Majority Leader Damon Thayer - S19 E26

- Sunday April 21, 2024 6:00 pm ET on KET2

- Sunday April 21, 2024 5:00 pm CT on KET2

- Sunday April 21, 2024 4:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Sunday April 21, 2024 3:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Sunday April 21, 2024 11:30 am ET on KET

- Sunday April 21, 2024 10:30 am CT on KET

Manny Caulk - Fayette Co. Public Schools - S11 E2

- Friday April 19, 2024 5:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Friday April 19, 2024 4:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Friday April 19, 2024 2:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Friday April 19, 2024 1:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Friday April 19, 2024 11:30 am ET on KETKY

- Friday April 19, 2024 10:30 am CT on KETKY

- Friday April 19, 2024 5:30 am ET on KETKY

- Friday April 19, 2024 4:30 am CT on KETKY

Kinship Care - S10 E46

- Thursday April 18, 2024 5:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Thursday April 18, 2024 4:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Thursday April 18, 2024 2:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Thursday April 18, 2024 1:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Thursday April 18, 2024 11:30 am ET on KETKY

- Thursday April 18, 2024 10:30 am CT on KETKY

- Thursday April 18, 2024 5:30 am ET on KETKY

- Thursday April 18, 2024 4:30 am CT on KETKY

Faith Politics - S10 E45

- Wednesday April 17, 2024 5:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Wednesday April 17, 2024 4:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Wednesday April 17, 2024 2:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Wednesday April 17, 2024 1:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Wednesday April 17, 2024 11:30 am ET on KETKY

- Wednesday April 17, 2024 10:30 am CT on KETKY

- Wednesday April 17, 2024 5:30 am ET on KETKY

- Wednesday April 17, 2024 4:30 am CT on KETKY

JoAnne Wheeler Bland - S10 E44

- Tuesday April 16, 2024 5:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Tuesday April 16, 2024 4:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Tuesday April 16, 2024 2:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Tuesday April 16, 2024 1:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Tuesday April 16, 2024 11:30 am ET on KETKY

- Tuesday April 16, 2024 10:30 am CT on KETKY

- Tuesday April 16, 2024 5:30 am ET on KETKY

- Tuesday April 16, 2024 4:30 am CT on KETKY

Andre Taylor - S10 E43

- Monday April 15, 2024 5:30 am ET on KETKY

- Monday April 15, 2024 4:30 am CT on KETKY

Devine Carama - S19 E25

- Sunday April 21, 2024 8:00 am ET on KETKY

- Sunday April 21, 2024 7:00 am CT on KETKY

- Saturday April 20, 2024 4:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Saturday April 20, 2024 3:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Sunday April 14, 2024 6:00 pm ET on KET2

- Sunday April 14, 2024 5:00 pm CT on KET2

- Sunday April 14, 2024 4:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Sunday April 14, 2024 3:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Sunday April 14, 2024 11:30 am ET on KET

- Sunday April 14, 2024 10:30 am CT on KET

Infant Nutrition and Breastfeeding - S10 E42

- Friday April 12, 2024 5:30 am ET on KETKY

- Friday April 12, 2024 4:30 am CT on KETKY

Cathe Dykstra - Family Scholar House - S10 E41

- Thursday April 11, 2024 5:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Thursday April 11, 2024 4:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Thursday April 11, 2024 2:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Thursday April 11, 2024 1:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Thursday April 11, 2024 11:55 am ET on KETKY

- Thursday April 11, 2024 10:55 am CT on KETKY

- Thursday April 11, 2024 5:30 am ET on KETKY

- Thursday April 11, 2024 4:30 am CT on KETKY

Gigi Butler - Gigi's Cupcakes - S10 E39

- Wednesday April 10, 2024 5:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Wednesday April 10, 2024 4:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Wednesday April 10, 2024 2:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Wednesday April 10, 2024 1:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Wednesday April 10, 2024 11:40 am ET on KETKY

- Wednesday April 10, 2024 10:40 am CT on KETKY

- Wednesday April 10, 2024 5:31 am ET on KETKY

- Wednesday April 10, 2024 4:31 am CT on KETKY

Cathy Zion - Zion Publications LLC - S10 E38

- Tuesday April 9, 2024 5:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Tuesday April 9, 2024 4:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Tuesday April 9, 2024 2:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Tuesday April 9, 2024 1:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Tuesday April 9, 2024 11:31 am ET on KETKY

- Tuesday April 9, 2024 10:31 am CT on KETKY

- Tuesday April 9, 2024 5:30 am ET on KETKY

- Tuesday April 9, 2024 4:30 am CT on KETKY

Josh Nadzam and Tanya Torp - S10 E37

- Monday April 8, 2024 5:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Monday April 8, 2024 4:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Monday April 8, 2024 2:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Monday April 8, 2024 1:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Monday April 8, 2024 11:30 am ET on KETKY

- Monday April 8, 2024 10:30 am CT on KETKY

- Monday April 8, 2024 5:30 am ET on KETKY

- Monday April 8, 2024 4:30 am CT on KETKY

Amy Goyer - Caregiving - S19 E24

- Sunday April 14, 2024 8:00 am ET on KETKY

- Sunday April 14, 2024 7:00 am CT on KETKY

- Saturday April 13, 2024 4:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Saturday April 13, 2024 3:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Sunday April 7, 2024 6:00 pm ET on KET2

- Sunday April 7, 2024 5:00 pm CT on KET2

- Sunday April 7, 2024 4:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Sunday April 7, 2024 3:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Sunday April 7, 2024 11:30 am ET on KET

- Sunday April 7, 2024 10:30 am CT on KET

Susan and Morgan Guess - S10 E34

- Friday April 5, 2024 5:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Friday April 5, 2024 4:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Friday April 5, 2024 2:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Friday April 5, 2024 1:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Friday April 5, 2024 11:30 am ET on KETKY

- Friday April 5, 2024 10:30 am CT on KETKY

- Friday April 5, 2024 5:30 am ET on KETKY

- Friday April 5, 2024 4:30 am CT on KETKY

Jay Williams - S10 E33

- Thursday April 4, 2024 5:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Thursday April 4, 2024 4:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Thursday April 4, 2024 2:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Thursday April 4, 2024 1:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Thursday April 4, 2024 11:30 am ET on KETKY

- Thursday April 4, 2024 10:30 am CT on KETKY

- Thursday April 4, 2024 5:30 am ET on KETKY

- Thursday April 4, 2024 4:30 am CT on KETKY

Kiley Lane Parker - S10 E29

- Tuesday April 2, 2024 11:30 am ET on KETKY

- Tuesday April 2, 2024 10:30 am CT on KETKY

- Tuesday April 2, 2024 5:30 am ET on KETKY

- Tuesday April 2, 2024 4:30 am CT on KETKY

Kevin Chapman - S10 E28

- Monday April 1, 2024 5:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Monday April 1, 2024 4:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Monday April 1, 2024 2:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Monday April 1, 2024 1:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Monday April 1, 2024 11:30 am ET on KETKY

- Monday April 1, 2024 10:30 am CT on KETKY

- Monday April 1, 2024 5:30 am ET on KETKY

- Monday April 1, 2024 4:30 am CT on KETKY

KCTCS President Ryan Quarles - S19 E20

- Sunday April 7, 2024 8:00 am ET on KETKY

- Sunday April 7, 2024 7:00 am CT on KETKY

- Saturday April 6, 2024 4:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Saturday April 6, 2024 3:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Tuesday April 2, 2024 5:00 am ET on KET2

- Tuesday April 2, 2024 4:00 am CT on KET2

- Sunday March 31, 2024 6:00 pm ET on KET2

- Sunday March 31, 2024 5:00 pm CT on KET2

- Sunday March 31, 2024 4:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Sunday March 31, 2024 3:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Sunday March 31, 2024 11:30 am ET on KET

- Sunday March 31, 2024 10:30 am CT on KET

Poet and Author Crystal Wilkinson - S19 E22

- Sunday March 31, 2024 8:00 am ET on KETKY

- Sunday March 31, 2024 7:00 am CT on KETKY

Kendell Nash - ECHO - S10 E27

- Friday March 29, 2024 10:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Friday March 29, 2024 9:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Friday March 29, 2024 2:00 pm ET on KETKY

- Friday March 29, 2024 1:00 pm CT on KETKY

- Friday March 29, 2024 11:30 am ET on KETKY

- Friday March 29, 2024 10:30 am CT on KETKY

- Friday March 29, 2024 5:30 am ET on KETKY

- Friday March 29, 2024 4:30 am CT on KETKY

Dorothy Edwards and Diane Fleet - S10 E26

- Thursday March 28, 2024 5:30 am ET on KETKY

- Thursday March 28, 2024 4:30 am CT on KETKY

Elaine Chao - S10 E23

- Wednesday March 27, 2024 10:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Wednesday March 27, 2024 9:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Wednesday March 27, 2024 5:30 am ET on KETKY

- Wednesday March 27, 2024 4:30 am CT on KETKY

Diabetes Epidemic - S10 E20

- Tuesday March 26, 2024 10:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Tuesday March 26, 2024 9:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Tuesday March 26, 2024 5:30 am ET on KETKY

- Tuesday March 26, 2024 4:30 am CT on KETKY

Mary Gwen Wheeler, 55,000 Degrees - S10 E16

- Monday March 25, 2024 10:30 pm ET on KETKY

- Monday March 25, 2024 9:30 pm CT on KETKY

- Monday March 25, 2024 2:21 pm ET on KETKY

- Monday March 25, 2024 1:21 pm CT on KETKY

Top